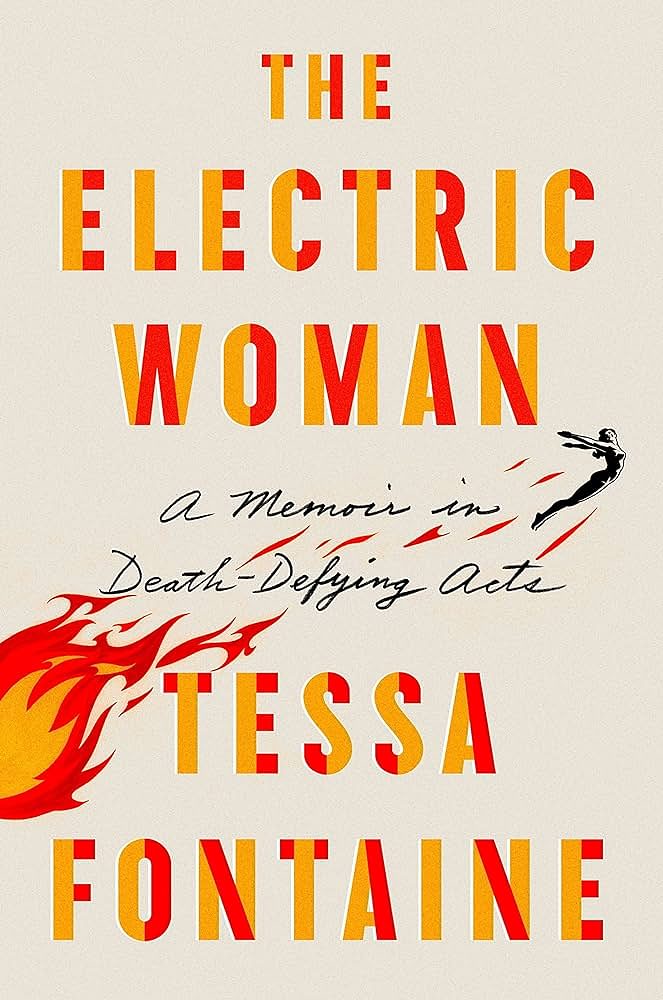

There's a moment in Tessa Fontaine's extraordinary memoir The Electric Woman: A Memoir in Death-Defying Acts where the owner of a sideshow tells her, now a performer, that they are "always playing. It's all just playing." That's a hard-won lesson. Two-and-a-half years after her mother has a near-fatal stroke, Fontaine sought solace and work and answers in a traveling sideshow -- a journey she'd only dreamed about -- where she meets a crew of varied people, the likes of which not seen often outside of a sideshow, unless one is out late at Walmart. While wandering the nation's fairgrounds with the troupe, Fontaine's mother and step-father do not resign to hospitals and tests in spite of the mother's brain leaking blood. Instead, they, too, seek adventure. In their cases, they board a ship to Italy for a trip they'd planned for years and years. While none of that story sounds pedestrian, the glut of memoirs can make even the most interesting works fall by the wayside. Don't let this one slip off the radar. It is a moving, gut-wrenching piece of work, and could easily go down as one of the best memoirs written. That's not hyperbole. Fontaine does magic herself outside of the World of Wonders: her writing is deep and lyrical and insightful and mesmerizing. But that doesn't make it easy. In fact, it's hard to read, at times, due to it being difficult not to personalize these anecdotes to one's own family. Throughout is a deep tenderness that elicits such strong sympathy from the reader; for example, in recounting her mother's trip across the ocean, Fontaine writes that if it were a painting "by one of the masters and not a quickly captured cell-phone snapshot, we'd discuss the brilliant use of light to illuminate the face, a bright wash across the skin so it seems to glow. Not the kind of light that has been still, like an ever-glowing constellation, but instead a kind of light in motion and a face that has just moved through darkness into the light." After all her mother had been through at that point, it's hard not to get choked up at the beauty of the scene, the beauty of us all, the devastating wonder of life. The book also brings to mind questions on how we, as regular people, can handle all of the stress, all the heavy burdens of life, all of the disasters, both imagined and awaiting. There's a certain juxtaposition between the liveliness and the still, both in the life of the carnival (and sideshow) with its short nights of quiet and her mother with her long stretches of silences and gentle humming as she slowly, slowly, slowly recovers. Very few memoirs move in such near-liquid form between morbidity and liveliness. The writing examines fully two things that cannot hold or last: life and the sideshow. Luckily, Fontaine's The Electric Woman is the first-hand account that will help it all alive forever in its own way. "Next comes the pin through a large pinch of skin on his neck," she writes about the human pin cushion act in the World of Wonders performed by the aloof performer, Red. "There's a little blood. I take a deep breath, dig in." She writes of his pain-inducing act, but it's clear at that point there's more at stake: getting through the tragedy of life as well. "I never had her," writes Fontaine about her mother years before her stroke occurs. It's a telling line in a book full of them, as lonely and longing and lovely as any.

There's a moment in Tessa Fontaine's extraordinary memoir The Electric Woman: A Memoir in Death-Defying Acts where the owner of a sideshow tells her, now a performer, that they are "always playing. It's all just playing." That's a hard-won lesson. Two-and-a-half years after her mother has a near-fatal stroke, Fontaine sought solace and work and answers in a traveling sideshow -- a journey she'd only dreamed about -- where she meets a crew of varied people, the likes of which not seen often outside of a sideshow, unless one is out late at Walmart. While wandering the nation's fairgrounds with the troupe, Fontaine's mother and step-father do not resign to hospitals and tests in spite of the mother's brain leaking blood. Instead, they, too, seek adventure. In their cases, they board a ship to Italy for a trip they'd planned for years and years. While none of that story sounds pedestrian, the glut of memoirs can make even the most interesting works fall by the wayside. Don't let this one slip off the radar. It is a moving, gut-wrenching piece of work, and could easily go down as one of the best memoirs written. That's not hyperbole. Fontaine does magic herself outside of the World of Wonders: her writing is deep and lyrical and insightful and mesmerizing. But that doesn't make it easy. In fact, it's hard to read, at times, due to it being difficult not to personalize these anecdotes to one's own family. Throughout is a deep tenderness that elicits such strong sympathy from the reader; for example, in recounting her mother's trip across the ocean, Fontaine writes that if it were a painting "by one of the masters and not a quickly captured cell-phone snapshot, we'd discuss the brilliant use of light to illuminate the face, a bright wash across the skin so it seems to glow. Not the kind of light that has been still, like an ever-glowing constellation, but instead a kind of light in motion and a face that has just moved through darkness into the light." After all her mother had been through at that point, it's hard not to get choked up at the beauty of the scene, the beauty of us all, the devastating wonder of life. The book also brings to mind questions on how we, as regular people, can handle all of the stress, all the heavy burdens of life, all of the disasters, both imagined and awaiting. There's a certain juxtaposition between the liveliness and the still, both in the life of the carnival (and sideshow) with its short nights of quiet and her mother with her long stretches of silences and gentle humming as she slowly, slowly, slowly recovers. Very few memoirs move in such near-liquid form between morbidity and liveliness. The writing examines fully two things that cannot hold or last: life and the sideshow. Luckily, Fontaine's The Electric Woman is the first-hand account that will help it all alive forever in its own way. "Next comes the pin through a large pinch of skin on his neck," she writes about the human pin cushion act in the World of Wonders performed by the aloof performer, Red. "There's a little blood. I take a deep breath, dig in." She writes of his pain-inducing act, but it's clear at that point there's more at stake: getting through the tragedy of life as well. "I never had her," writes Fontaine about her mother years before her stroke occurs. It's a telling line in a book full of them, as lonely and longing and lovely as any.